To what extent is Waiting for Godot a play about the condition of being constrained?

An interpretation of Samuel Beckett's play

This literary essay considers to what extent Waiting for Godot is a play about the condition of being constrained? I hope you enjoy reading! I loved writing this as this play is one of my favourites.

It is useful to explore Samuel Beckett’s play focussing on the condition of being constrained as it provides a foundation to interpret the play that has become to be defined as ‘acontextual’ (Gupta, 2005, p.239). The acontextual quality emphasises the play’s theme of constraint. It is because it evades an assigned context that the constrained condition of the characters’ circumstances – which govern their interactions and actions – can be applied broadly to other contexts and represent the human condition within those contexts. Looking at the significance of the stage directions and props, the pattern of the plot, and the language used provides a way of interpreting the play’s meaning aligned with the condition of being constrained. It also gives opportunity to see how these elements of the play interact with, if only momentarily, a particular reading in either a religious or philosophical context. It is only momentarily as the play neither propounds nor excludes ideologies definitively.

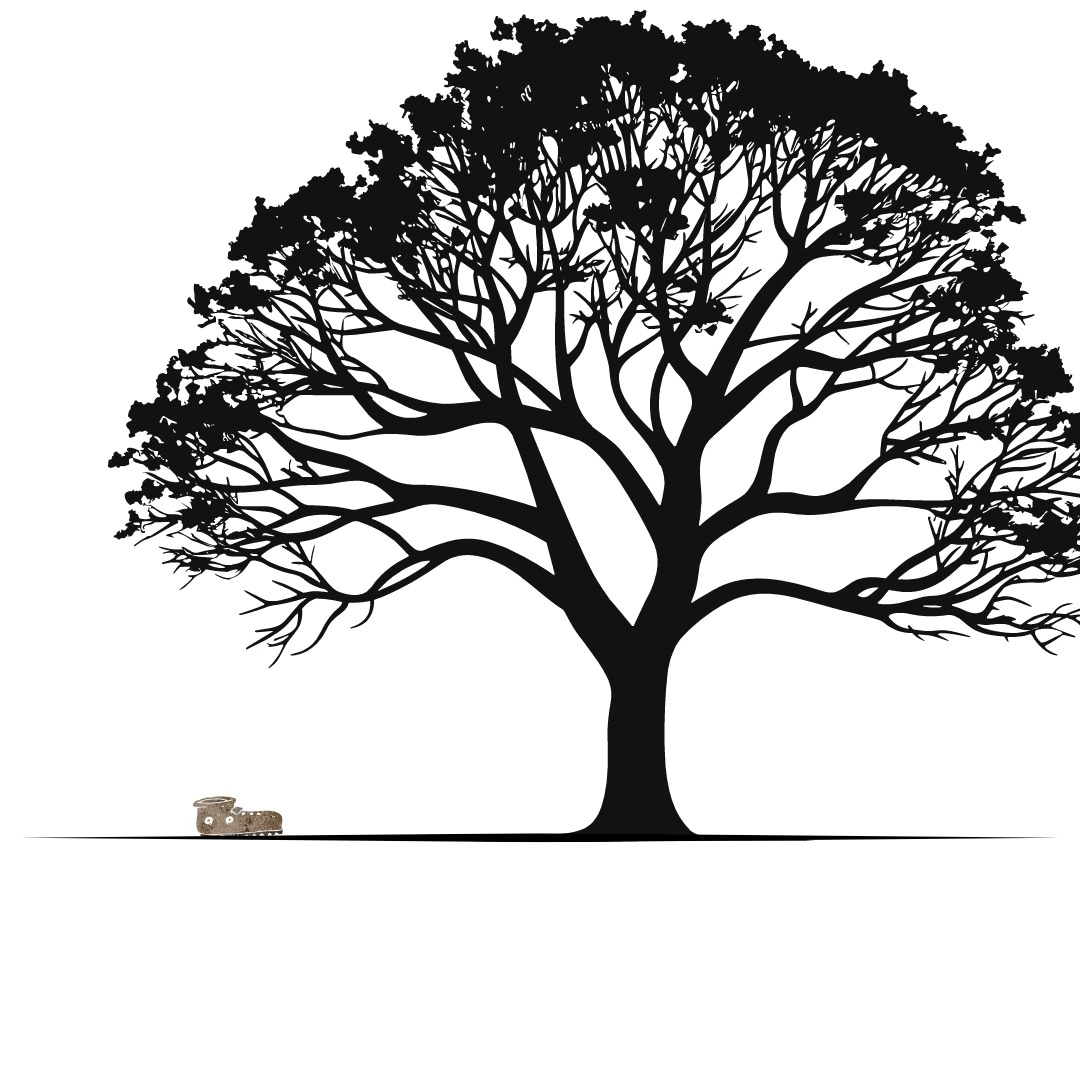

At the beginning of act one the stage directions coupled with the references to the props establishes the constrained context that the characters’ live in. The stage directions show Estragon to be engaged in ‘trying to take off his boot’ and, having pulled at it with both hands, he ‘gives up exhausted’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], p.1). Importantly to augment the theme of constraint, Estragon repeats the action but fails as ‘before’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], p.1). The dynamic between Estragon’s attempts and failures to remove his boot demonstrates and foreshadows how the characters’ actions and difficulties of understanding will consist of the same pattern: attempting but failing to fully understand or act in a fully autonomous manner. The boot therefore becomes a prop which, after Estragon has removed it, fulfils the function of symbolising constraint because the boot has been removed from its purpose: that of travel. The fact that it has been placed on the stage provides a visualisation of how the characters are – and will continue to be – circumscribed by metaphorical and physical stasis. This conception of stasis coupled with the stage directions and props at the beginning of act two develops the constrained circumstances that the characters are in. Vladimir’s observation in act one that the tree ‘must be dead’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], p.5) and the stage directions in act two that the tree now ‘has four or five leaves’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], p.47) pits the characters’ stasis against nature’s natural cycle represented by the new leaves. Like the boots, the tree’s leaves – as props – come to emblematise the characters’ consistent state of being constrained: the tree’s leaves suggest renewal – taken place over a period of time – but for the characters, we are told, it is only the ‘Next day. Same time. Same place’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], p.47). Therefore, the time imbalance between the time past for the natural world and for the characters highlights their continued, constrained condition: nature will continue to change and be renewed in a way that the characters will not.

The rope as a prop that is used by Pozzo to leash Lucky shares the same level of symbolic importance as the boots and the tree in representing the constrained. The stage directions indicate clearly the hierarchical relationship between Pozzo and Lucky by stating that ‘Pozzo drives Lucky by means of a rope passed round his neck’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], p.13). The relationship between them is subject to slight change when, in act two, the stage directions qualify that ‘Pozzo is blind’ but the rope is ‘as before, but much shorter, so that Pozzo may follow more easily’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], p.66). The rope’s presence and change in size indicates a shift in the dynamic of Pozzo’s and Lucky’s relationship but it doesn’t fully alter the dependency that they have on each other (Gupta, 2005, p.247). This transfers over and expresses the dependency of Vladimir’s and Estragon’s relationship: the stage directions of ‘They do not move’ at the end of both acts (Beckett, 2004, [1955], pp.46, 82) in conjunction with Estragon’s suggestions that they would either ‘have been better off alone’ or that it would be ‘better for’ them if they parted (Beckett, 2004, [1955], pp.46, 82) illustrates their constrained relationship. The rope then comes to represent constraint of all the characters involved by establishing the physical connection between Pozzo and Lucky and the figurative connection between Estragon and Vladimir. The acontextual quality of the play lifts the notion of interconnectedness shared between the characters to all humanity: here the existentialist notion that everyone is responsible for themselves and free (Gupta, 2005, p.245) is being challenged as it appears from the text that the characters are bound to and constrained by one another.

The condition of being constrained can be contextualised by the repetitions that occur in the plot. At the beginning of act one, for example, Vladimir says to Estragon ‘So there you are again’ and at the beginning of act two he says similarly ‘You again!’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], pp.1, 48). The repetition is enlarged by Vladimir’s following question – occurring in both acts – to Estragon concerning who ‘beat’ him (Beckett, 2004, [1955], pp.1, 48). The repetition here occurs a day apart and coupled with the exclamation mark in ‘You again!’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], pp.48), which draws attention to the predictable patterning of the characters’ lives, is suggestive of the limited and constrained existence that the characters have lived and will continue to live in. Depending on the emphasis of the word ‘again!’ in Vladimir’s speech it could also suggest disbelief on Vladimir’s part at the two having met again. This would be in line with the play’s ‘virtue of the inability to be certain’ (Gupta, 2005, p.249) and connects it with other passages that question the reality of existence; and in this manner the characters are constrained by being denied unequivocal understanding. For example, the character named Boy appears twice and his later interaction with Vladimir and Estragon mirrors his first. In act one Vladimir questions whether the boy ‘did see’ them and in act two more emphatically he says ‘You’re sure you saw me, you won’t come and tell me tomorrow that you never saw me!’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], pp.44, 81). The stage direction states too that Vladimir vocalises this with ‘sudden violence’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], p.81) which compounds the repetition that has taken place, and the severity of the circumstances Vladimir and Estragon are in: they are constrained by an inability to fully comprehend what has empirically taken place.

There is a repetitious through-line in the play which serves to reinforce the cyclical nature of the events of the characters’ lives, and it also shows the extent of their constrained condition. Each revolution of the phrase ‘We’re waiting for Godot’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], pp.5, 40), including its slight variation to the future tense in ‘To wait for Godot’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], p.80), demonstrates their temporal and spiritual constraint – to the physical location and to the ethereal belief that they will meet Godot. The stage directions after each time the phrase is used states there is to be a ‘pause’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], pp.5, 40, 80) which signifies the importance of the through-line. The significance of such a through-line reduces the acontextual nature of the text to one that is concerned with how humankind interacts with religion or the transcendental. The faith that Vladimir and Estragon show in waiting for Godot to appear is akin to the faith that the participants of monotheistic religions have. The equivocal nature to the characters’ existence – observable in, for example, their interactions with the boy, the ambivalence of time seen in the growth of the tree’s leaves and their constant uncertainty about Godot’s appearance – includes not only the uncertainties in the empirical but also in the spiritual, transcendental realm. Constraint then manifests in the physical act of waiting and in the spiritual act of waiting for Godot or God (Gupta, 2005, p.243).

Along with the stage directions and props and the patterns within the plot, the language used is another way to interpret the play’s theme of constraint. Just as there are repetitions in the plot, repetitions occur within the language to the extent that the vocabulary is shared by the characters. In the beginning of act one Estragon says ‘Nothing to be done’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], p.1) and shortly afterwards Vladimir mirrors the sentence when he too says ‘Nothing to be done’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], p.3). The mirroring helps summate their thoughts towards the constrained context of their physical environment. Mirroring of language that occurs elsewhere serves to express their feelings in an ironical manner which locates their constraint internally and metaphysically. Vladimir wants Estragon to say ‘“I am happy”’, to which he replies: ‘I am happy’; both characters then repeat the phrases ‘So am I’ and ‘We are happy’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], p.50). The quickness and the shortness of the replies indicate that both are constrained to the point where their prosaic language mirrors one another, producing an overtly ironical message which actually conveys their constrained unhappiness. The language used by Pozzo towards Lucky is utilised by Vladimir towards Estragon, signifying the narrowed vocabulary and interconnectedness between them all thus reaffirming the constrained context. Pozzo’s reference to Lucky as a ‘Pig!’ Beckett, 2004, [1955], p.p33) is used by Vladimir when he later calls Estragon a ‘Pig!’ and a ‘Hog!’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], pp.56, 59) and, at Vladimir’s request, Estragon says to him ‘Think, Pig!’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], p.62). The manner in which these characters utilise the same modes of expression is suggestive of a narrowed and thus constrained vocabulary to match their existence.

Providing a contrast to Vladimir’s, Estragon’s, and Pozzo’s language is Lucky’s speech. It contrasts their often-quick replies and similarities, and sharply contrasts Vladimir’s and Estragon’s inability to ‘Say something!’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], p.53) in act two – an interaction between them that is formed by short replies such as ‘They rustle/They murmur/They rustle’ and punctuated by the stage directions of: ‘Silence’ and ‘Long silence’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], p.52). Lucky’s speech is the longest vocalised by any of the characters, is unpunctuated and proliferates at the end (Gupta, 2005, p.241). Its volume and diversification of topics and associations – including God, sports, locations and topography (Beckett, 2004, [1955], pp.34-36) – and its function of presenting them in a seemingly ‘haphazard fashion’ (Gupta, 2005, p.241) ensures a level of scrutiny towards it because of its uniqueness in the play and, therefore, a piqued awareness of the more limited, repetitious, shared and constrained vocabulary of the other characters. The language used then provides another way to represent the characters’ constrained context.

Looking at the play’s stage directions and props, patterns within the plot, and the language used has supported the thematic interpretation that the play is about the condition of being constrained. Constraint provides a foundation to interpret the play’s meaning and is found in the symbolism of the props, the significance of the repetitions in the plot and in the shared vocabulary of the characters. Each of these elements point towards the condition of being constrained and when they are considered together it is clear that physically, figuratively, emotionally and intellectually the characters will not be offered any succour to their constrained context. The acontextual qualities of the play allow for momentary contextual readings – that of philosophy and religion – to negotiate the characters’ circumstances but it is not consistent. The characters’ existence denies such readings as they exist in a time not identifiable, in a place unidentifiable, and engage with what should be evidentially observable in an unsuccessful manner to the extent where their constrained existence gives them only ‘the impression’ that they ‘exist’ (Beckett, 2004, [1955], p.58).

Thank you for reading one of my essays on literature. I hope you enjoyed it. Please feel free to comment and check out my other writing across my Substack.

Bibliography

Beckett, S. (2004) ‘Waiting for Godot’ Samuel French LTD

Beckett, S. [1949] ‘Three dialogues’ in Gupta, S. and Johnson, D. (ed.) A Twentieth-Century Literature Reader: Texts and Debates (A300 Reader), Routledge in association with The Open University, Milton Keynes, pp.233-235

Bertens, H. [1995] ‘The Idea of the Postmodern’ in Gupta, S. and Johnson, D. (ed.) A Twentieth-Century Literature Reader: Texts and Debates (A300 Reader), Routledge in association with The Open University, Milton Keynes, pp.235-243

English, F, J. [2002] ‘Winning the Culture Game: Prizes, Awards, and the Rules of Art’ in Gupta, S. and Johnson, D. (ed.) A Twentieth-Century Literature Reader: Texts and Debates (A300 Reader), Routledge in association with The Open University, Milton Keynes, pp.243-255

Gupta, S. (2005) ‘Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot’ in Johnson, D. (ed.) The Popular and the Canonical (A300 Book 2) Milton Keynes, The Open University, pp.210-261